America Gets Dumber: Stupidity, Elections, and Tantrums of White Entitlement

20 March 2022

America Gets Dumber: Stupidity, Elections, and Tantrums of White Entitlement

Economic anthropologist David Graeber revealed a fact that many observers had described as a puzzle: significant parts of the American white working class voted against their economic interests but aligned with their perceived values. They are trading “bread-and-butter†economic issues for cultural ones (Graeber). And this was not a one-and-off situation. The puzzle of the white working-class re-electing Bush was repeated in the election of Donald Trump in 2016. As a result, George W. Bush was re-elected while cutting taxes for the rich, waging an expensive war in Iraq, and increasing public debt to unprecedented levels. The debates, more than anything else, left most of the American liberal intelligentsia reeling because they took it as proof of what they had suspected: all things they most hated about Bush were exactly what so many Americans liked about him. It was hard to escape the impression that, in the end, Kerry’s articulate presentation, and his skill with words and arguments, counted against him. Graeber and others have argued that large sectors of the white American working class were disappointed with liberal politicians because they associated them with a cultural elite that occupied positions in society, allowing them to pursue careers of intrinsic value in the arts, science, or politics but which were largely closed to the working class.

What follows is an effort to understand a very concrete, immediate political question: What is the strange appeal of right-wing populism to large sections of the white American working class? In What’s The Matter With Kansas, authors like Tom Frank laid out the problem: in much of the US, insofar as the white working class is drawn to radical politics of any sort, it is far more likely to be the far Right. This question became unavoidable with the 2004 re-election of George W Bush. It appeared to reflect something fundamental about Bush’s popular appeal: the very qualities they interpreted as pig-headed stupidity – the stubborn determination to take simple policy positions and then stick with them no matter how unwise, disastrous, or simply factually incorrect their basis may turn out to be – seemed to be viewed as moral strength or decisive leadership. One might say the liberal intelligentsia, in their confusion, was demonstrating just how out of touch with most Americans they were. Still, there is a legitimate puzzle here. After all, as Graeber notes, Bush does come from one of the most elite families in the country; he attended Andover, Yale, and Harvard; he has been known to refer to the wealthiest class of Americans as his ‘base.’ How could such a man ever be taken as a ‘man of the people’?

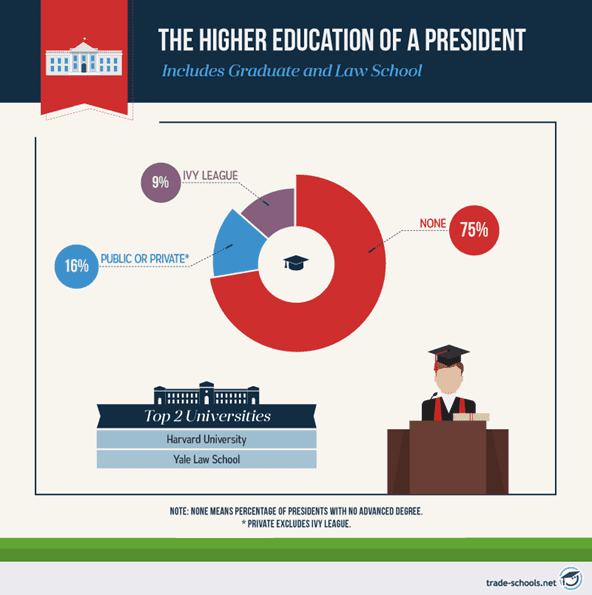

As they say, the plot thickens. The real dilemma is how the trend Graeber identified in the re-election of George W. Bush in 2004 against John Kerry was virtually duplicated in the election of Donald J. Trump in 2016. Consider Donald Trump’s win as 2004 George W. Bush on steroids. If you were like most people, you didn’t see it coming. However, 59 million-or-so voters who elected Donald Trump, the 45th President of the United States, were ecstatic the night of November 8th, 2016, when he won. Looking at demographics reveals a clear history of white entitlement and resentment born of backlash. It’s clear a people who idolize stupidity might vote against their own interests. Ignoring Trump’s tax breaks for the rich simply because they were suckered by his “manly†rhetoric, white working-class voters once again proved that they desperately sought common ground with power just as long as it neither looked nor sounded elitist. Still wounded by the supreme eloquence and evident intelligence of outgoing President Barack Obama, the first Black president of both the nation and, more tellingly, of the Harvard Law Review, they eagerly sought the face of Stupidity 2.0 in Trump, the first president in recent history to hold only a bachelor’s degree rather than the Masters (or higher), which even Bush 2

holds. This heavily constructed narrative of getting a “Washington outsider,†as then 70-year-old Trump coined himself to conjure up images of the “good old days†back when white men could rise to even the Presidency without an education, as the chart to the right shows, was just the alliance sought by many working-class whites who still felt snubbed at having not only a then 47-year-old Black man inaugurated into the Presidency, but also one holding degrees from two Ivy League schools. Duped by the promise of the return of rust belt jobs and the revival of coal mines that never materialized, these economically struggling working-class whites ignored that the president cut taxes for the wealthy. They were infatuated because he used the same overly simplistic language of “winners†and “losers†and “Make America Great Again†over a cold can of Budweiser, plying what renowned UC Berkeley linguist George Lakoff calls “basic [linguistic] mechanisms,†verbal moves that Trump makes “instinctively to turn people’s brains toward what he wants: Absolute authority, money, power, celebrity†(Lakoff). Tracing the desperation and fear of white American voters holding on to fading power, we can understand how white Americans will not only work against their own socio-economic interests, but more importantly sow the seeds of destruction in the nation they claim to love the most.

At the root of this resurgence of valorizing stupidity – clearly a twisted kind of claim to old-fashioned “family values†(Graeber) — was this anti-intellectual sentiment that pushed white Americans to elect Trump, another elitist, into the White House. Few thought the 2016 election would result in a man with an elitist background, no political or military service leading the free world. Trump’s administration was preceded by eight years of Barak Obama’s presidency. It’s clear that Trump’s legend sprung from a backlash against the election of the first Black president. With a white face once again in the White House, white people were very willing to overlook his buffoonery, as Trump himself noted, “I could shoot someone in the middle of Times Square and get away with it.â€

The Stupidity 2.0 era also relies on class resentments, as the backlash of Trump’s election was driven by massive support from the working-class white men, who were offended by the election of Barack Obama, the first Black president of the United States. As a result of their racial antagonism, they turned out in astounding numbers, as mainly white, working-class counties around the country flooded to the polls. The surge in the polls provided President-elect Trump more support in many areas, even the ones that supported President Barack Obama back in 2012.

Quite a stunning reversal. Approximately 72 percent of white men, with no college degree voted for Donald Trump. Four-in-ten voters (39 percent) were looking for a candidate who could bring about change; Those voters favored Trump, 83-14 percent.

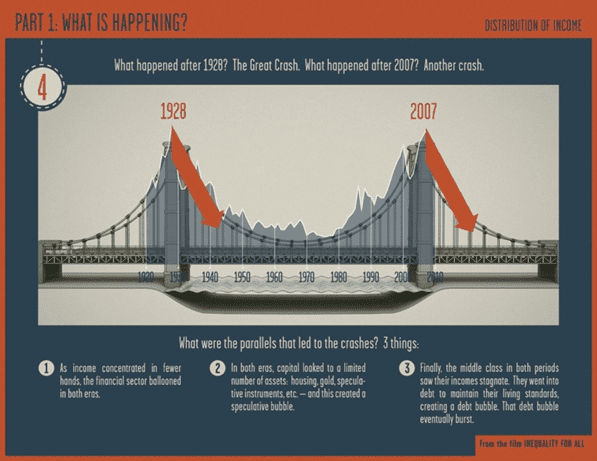

Americans have always seen the United States as a land of opportunity. From the perspective of an immigrant from Haiti or Bangladesh, it continues to be one. America has always been a country built on the promise of unlimited upward mobility. The remarkable thing is how little the discourse has changed with the changing statistical reality. Free market enthusiasts (a category that includes all promoters of mainstream social and economic discourse in the US) insist that the US is, as Larry Elder recently put it, ‘the most upwardly mobile country in history’ (Elder, 2007). However, the harsh truth is class mobility in the US peaked in the 1960s and has declined ever since. This has left the US with the lowest rate of intergenerational class mobility among industrialized democracies (e.g., Beller and Hout, 2006; Blanden et al., 2005). This appears to be partly because the gap between rich and poor is so vast, as we see in the chart above right from economist Robert Reich’s documentary, Inequality for All (Kornbluth). With the gap between the richest and the rest of us growing since Reagan’s tax breaks for the rich, it’s no wonder we end up with disgruntled whites willing to do almost anything to feel connected to the wealthiest. But no amount of wishful thinking can bridge that gap, as it is increasingly difficult to cross class lines, partly because of the increasing cost of higher education.

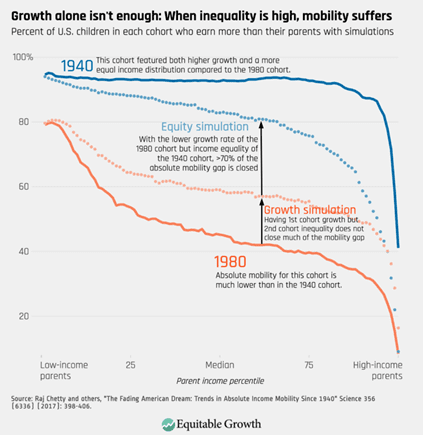

What’s also driving the white American infatuation for Trump-era Stupidity 2.0 is the long-standing myth that upward income mobility is endless. The chart below points out errors of those beliefs. Most Americans still sadly believe that the working-class condition is just a way station: something individuals or families pass through on the road to something far better. This is a conception that goes back at least to the late Middle Ages (Graeber, 1997; Laslett, 1972), where working for others was considered essential to the status of youth, but the vision of their own society far longer than almost anywhere else. Abraham Lincoln, for example, would regularly respond to little different from the more literal variety by arguing that wage labor in the North was in no sense a permanent condition. Factory work was seen as the province of first-generation immigrants, whose children, at the very least, could be expected to pass on to something else – at the very least, to acquire some land and become a homesteader on the frontier. What matters here is not so much whether this was true but that it seemed plausible to most Americans at the time. Ain’t so, Joe! As Bugs Bunny always said, “That’s all, folks!†But there is no joke here.

Graeber rightfully points out that whenever roads to upward mobility opportunity get “clogged, profound unrest results,†but today’s white unrest stems from not just crowded university classrooms and increased competition in the workplace but rather the perception that people of color hold both their seats in class and their place at work that they deem rightfully theirs.†The educational system quickly got clogged, Graeber points out, at after World War II the educational system grew rapidly because the GI Bill poured “huge resources into expanding the higher education system,†allowing a mostly white GIs to suddenly throw themselves into higher education with plenty of funding and resources just for them. In the 1970s, the resources in the GI Bill were significantly reduced. And now colleges and universities are increasingly diverse. White working-class Americans’ enrollment numbers dropped. leading the exit of the myth that a young person does not need the education to succeed in industrial, But there are far fewer manufacturing workers overall, with about 7.5 million jobs lost since 1980. These job losses have likely contributed to the declining labor force participation rate of prime-age (between the ages of 21 and 55) U.S. workers. In “The transformation of manufacturing and the decline of U.S. employment†(National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 24468, March 2018), economists (Kerwin Kofi Charles, Erik Hurst, and Mariel Schwartz) examine the factors that have played a role in the decline of prime age manufacturing workers since 1980 and focusing in the 2000s.

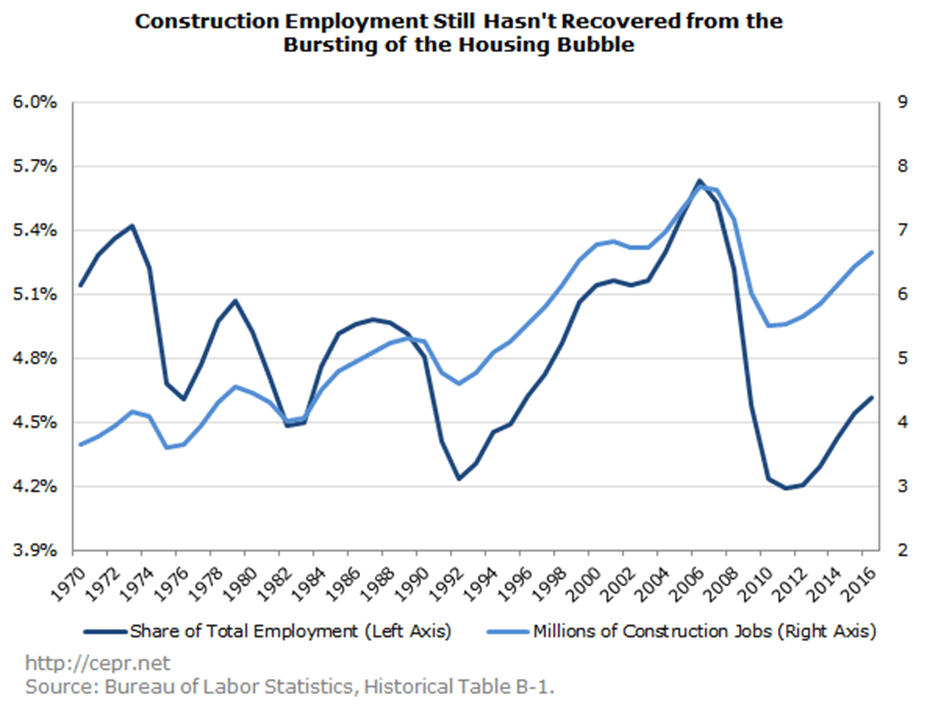

Construction follows a somewhat different pattern. Construction employment is highly cyclical following patterns in the housing market following the ups and downs in the business cycle, but it has a little clear secular trend. In 2016, 4.7 percent of the workforce was employed in construction (6.7 million workers), with the figure heading upward over the year. This is down from the 5.2 percent figure for 1970 but not out of line with the average for that decade.

The National Trend in Mining Jobs

Mining employment has largely followed the path of world energy prices as the bulk of employment in the sector is energy-related. Employment in the sector rose through the 1970s and peaked in 1982 at 1.2 percent of total employment. The collapse in world energy prices sent employment in the sector sharply lower in the next two decades, with employment in mining falling to just 0.4 percent of total employment in 1998. Higher energy prices and the fracking boom increased mining employment from 2003 until 2014. Since then, the plunge in energy prices sharply reduced employment, so it again stands at just 0.4 percent of total employment, with 626,000 total jobs in the sector.

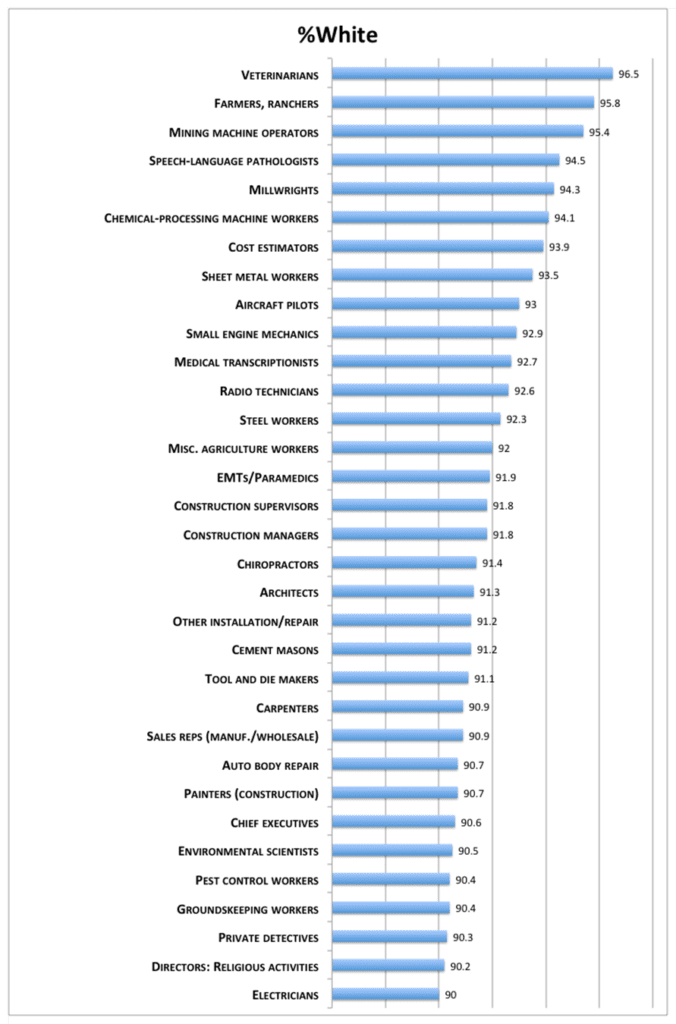

Every occupation that’s more than 90 percent white, according to the BLS, includes vets, CEOs, and private detectives.

(DerekThompson) The workforce is even more stratified by race than you’d imagine. The differences in unemployment, participation, and average earnings between whites, blacks, and Hispanics aren’t just stark. They’re also sturdy, rarely yielding over the last 40 years.

The racial gaps are stark at the job level, too.

Whites account for about 81 percent of the workforce. But there are 33 occupations counted by the BLS (particularly those on farms, around heavy machines, in doctor’s offices, and in C-suites) where whites officially account for nine in ten workers or more. Here they are:

I’m passing this along, not because I think it tells us something extraordinarily new, but as a side salad to this long piece about jobs and race. Still, I’d be fascinated to hear theories about the list because I’m not even going to try. Asians account for 20 percent of physicians and surgeons but just 1 percent of vets. Ground cleaning/maintenance workers are 44 percent black, but groundskeepers are 90 percent white. I don’t know why; maybe you do.

UPDATE: Looking over this list, you might have noticed that many occupations are skilled construction jobs, such as electricians and carpenters. That’s not a coincidence. Trade unions have had a complicated and often ugly history with race that’s helped shut blacks and Hispanics out of these highly coveted lines of work. In 2005, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote about the impact on Chicago’s South Side:

“Chicago is a union town. But in Mitts’ ward–and among many poor blacks–some unions rank only a couple of notches above the Ku Klux Klan. Black leaders in Chicago have repeatedly charged that the building trades unions, traditionally controlled by whites, are keeping a grip on jobs. While 37% of Chicago is black, only 10% of all new apprentices in the construction trades between 2000 and 2003 were black, according to the Chicago Tribune.” [Derek Thompson is a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of the Work in Progress newsletter. He is also the author of Hit Makers and the host of the podcast Plain English.]

The Cold War social contract was not just a matter of offering a comfortable life to the working classes but also a matter of offering at least a plausible chance that their children would not be working class.

Graeber argues dramatically lacking in debates about identity politics are identities like, say, ‘Baptist’ or ‘Red neck’ – that is, those that encompass the bulk of the American working class, who are made to vanish rhetorically at the same time as their children are largely excluded from college campuses and all the social and cultural worlds college opens. Their reaction to their children’s exclusion from this means of upward mobility is, predictably, a tendency to see social class as largely a matter of education and an indignant rejection of the very values from which white majorities are effectively excluded. As Tom Frank has recently reminded us, the hard Right in the US is largely a working-class movement, full of explicit class resentment. David Graeber reminds us, “their hatred is directed above all at the ‘liberal elite’ (with its various branches: the ‘Hollywood elite,’ the ‘journalistic elite,’ ‘university elite,’ ‘fancy lawyers,’ ‘the medical establishment’ [think Dr. Anthony Fauci]). The sort of people who live in big coastal cities, watch PBS or listen to NPR†— or even more, those who might be appearing in or producing programming for CNN, MSNBC, PBS, or NPR.

Why do working-class Trump and Bush-type voters resent intellectuals as a class more than rich people? David Graeber says that the answer is obvious. They do because they can “imagine a scenario in which [… one] of their children might one day become rich, but cannot possibly imagine one in which … their children†— no matter how talented – “would become a member of the liberal intelligentsiaâ€](Graeber). Graeber insists that this is:

not an unreasonable assessment,†for the child of a truck driver “from Wyoming might not have much chance of becoming a millionaire, but it could happen. Certainly, it’s much more likely that him ever becoming an international human rights lawyer, [ a host on CNN], or a drama critic for The New York Times. Such jobs go almost exclusively to children of privilege. Insofar as there are not quite enough children of privilege to go around – since elites almost never produce enough offspring to reproduce themselves demographically – the jobs are likely to go to the most remarkable children of immigrants. [And] executives with Bank of America, or Enron, when facing a similar demographic problem, are much more likely to recruit from poorer white folk like themselves. (Graeber)

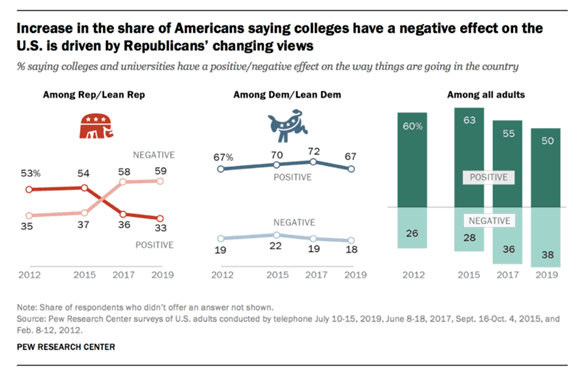

Ultimately, using backlash positions as a basis for voting rips at the very fabric of democracy, for not only are a large portion of Americans – white working-class people – voting against their own economic interests, they are deepening the national divide by pitting the educational system against ‘all things American,’ as if education is ‘bad for America,’ as a rapidly increasing portion of Republicans now report, as seen in the Pew Research data shown to the right. Interestingly, right at the time that an increasingly number of people of color are a rising and important presence on college campuses across America, a significant portion of unschooled, resentful whites continue to not only bash education, but more importantly, praise and uphold stupidity 2.0 as the hallmark of being a good patriot. Indeed, with anti-intellectualism in America pre-dating even the Bush era, as noted by 1964 Nobel Prize-winning historian Richard Hofstadter’s acclaimed work Anti-Intellectualism in America (Masciotra), it’s no wonder it’s settled into the nation’s “values†(Graeber), casting education and intellectualism into “frames†(Lakoff) that define what’s sufficiently ‘patriotic,’ and what is not.

(By Jessica Irvine)

It is the basic yardstick of progress that every generation should live better than the last.

For women, there has never been a better time to be alive. We vote we work; we have control of our bodies and fertility. While there’s much progress still to be had, the progression of women in society has generally been an upward trajectory.

When discussing changes to race hate laws, the One Nation leader has called on people to understand the meaning of the word racist before calling her one.

Daughters today enjoy greater income-earning capacity and status in the workforce than their mothers.

Every decade since the 1970s, the share of women working in the lowest fifth of skilled jobs has shrunk, according to a recent analysis by Michael Coelli and Jeff Borland titled Job Polarization and Earnings Inequality in Australia.

And every decade, the proportion of women working in the highest fifth of jobs by skill level has risen.

Coelli and Borland use occupational earnings data as an indicator of job skill level. So it’s also true to say that more women are working in high-paid jobs, and fewer in low-paid jobs.

But the same cannot be said for men.

True, the proportion of men working in the highest fifth of skilled jobs rose in every decade, but to a lesser extent than the gains for women.

But crucially, the share of men working in the lowest skilled jobs also rose in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, although not in the 2000s.

When it comes to the workforce, it is far from clear that men today fare better than their fathers.

While the female workforce has experienced a general increase in skills, the male workforce has become more polarized – with more men working at the top and bottom of the skills ladder.

“Job polarization in Australia has mainly been a male phenomenon,” the economists conclude.

The biggest “male losers”, according to their analysis of changes in occupation by gender, have included metal fitters and machinists, factory hands, trades assistants, truck drivers and electrical engineers.

The biggest “male gainers” have included computing professionals, sales assistants, cooks, and kitchen hands.

Secure, full-time jobs in traditionally male occupations have been replaced by often part-time jobs in fields that previously would have been classified as “women’s work.â€

This loss of secure, full-time, traditionally male jobs is fueling an undercurrent of dissatisfaction among working-class men that is being increasingly exploited by charismatic politicians.

Make no mistake, the rise of the political parties led by Donald Trump and Pauline Hanson is part of a backlash against the advancement of women and minorities into the workforce and the overturning of traditional male breadwinner models.

If you assume that power and status are relative concepts – gains must be offset by losers – then the advancement of women and minorities in society is a direct challenge to the power of white men.

Could this be the source of the new rage and anger that has infected politics globally and at home?

Dr. Michael Currie, a clinical psychologist, psychoanalyst, and author of several books on anger, says anger is often a consequence of a person feeling wronged.

” ‘Someone hurt me, so I have to hurt them’ is the cognitive component of anger; the action urge is to strike out,” says Currie.

“From a psychological point of view, some white working-class men have felt hurt in one way or another by what is seen as the ruling class in Washington. Standing at the head of that are people like Obama and Clinton.

“It is not via rationality that they would want to vote for this brash, unqualified rogue [Donald Trump]. But, in a way, it feeds into their wish to strike out and hurt. It sort of makes sense to some people. People feel hurt by what’s happened to them; therefore, voting for Trump is possibly a way of striking out at that hurt.”

Currie says it is fundamental in human nature to compare oneself to one’s parents.

“Of course, the child always looks up to the father. It’s a very old tendency in Western patriarchy, causing a crisis for men.”

Given changes in the workforce, “if the recent economic data is borne out psychologically for a few generations, some men are vulnerable to feeling condemned to being part of a race of failures.

“Men aren’t doing as well as their dads.”

“On a psychological level, there is some truth to the angry white man phenomenon. Many feel like they can’t do what they used to be able to.”

White man rage may not be rational. And it by no means afflicts all men. But for some, it is a real emotion, deeply rooted in real-world causes.

Traditional middle-income male jobs have been lost and are not coming back soon.

The key must be to reform male stereotypes to put a value on flexible work and work in the health and caring industries where all the jobs growth is.

Changes in the workplace have been unfolding rapidly. Changes in social attitudes will take much longer.

Works Cited

Clemens, Austin. “Eight Graphs That Tell the Story of U.S. Economic Inequality.†Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 9 Dec. 2019, https://equitablegrowth.org/eight-graphs-that-tell-the-story-of-u-s-economic-inequality/. Accessed 17 March 2022.

Garafoli, Joe. “GOP RHETORIC / Bush Puts His Own Spin on ‘Freedom’ / Left’s Mainstay Word Recast in Economic Terms, Analyst Says.†SF Gate, SF Gate, 21 Jan. 2005, https://www.sfgate.com/politics/joegarofoli/article/GOP-RHETORIC-Bush-puts-his-own-spin-on-2736914.php. Accessed 17 March 2022.

“Getting Political with Education.†Trade Schools: Find Vocational Training for a Successful Career!, 24 June 2020, https://www.trade-schools.net/learn/presidential-colleges. Accessed 17 March 2022.

Graeber, David. “The Political Metaphysics of Stupidity.†Rpt. in The Blue Book: The Collected Readings of English 3. Comp. by Margaret Shannon, English Department, Long Beach City College. Long Beach, CA: Online Canvas Course, 2022. 62-70.

Kornbluth, Jacob, director. Inequality for All. Inequality for All, Anchor Bay Entertainment, 2014. Accessed 17 Mar. 2022.

Lakoff, George. “Understanding Trump.†University of Chicago Press, Aug. 2016, https://press.uchicago.edu/books/excerpt/2016/lakoff_trump.html. Accessed 17 March 2022.

Machiavelli, Niccolò. “The Circle of Governments.†Rpt. in The Blue Book: The Collected Readings of English 3. Comp. by Margaret Shannon, English Department, Long Beach City College. Long Beach, CA: Online Canvas Course, 2022. 52-54.

Masciotra, David. “Anti-Intellectualism Is Back – Because It Never Went Away. and It Has Killed 100,000 Americans.†Salon, Salon.com, 30 May 2020, https://www.salon.com/2020/05/30/anti-intellectualism-is-back–because-it-never-went-away-and-its-killing-americans/. 17 March 2022.

Parker, Kim. “The Growing Partisan Divide in Views of Higher Education.†Pew Research Center, Pew Research, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/08/19/the-growing-partisan-divide-in-views-of-higher-education-2/. Accessed 17 March 2022.

Rock, Chris. Bigger and Blacker. Dir. by Keith Truesdell. HBO Studios, 1999.

Schaeffer, Katherine. “Racial, Ethnic Diversity Increases Yet Again with the 117th Congress.†Pew Research Center, Pew Research, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/28/racial-ethnic-diversity-increases-yet-again-with-the-117th-congress/. Accessed 17 March 2022.